When Ansel hired me in July of 1974 to be his assistant in Carmel, he actually hired me to be his #2 assistant. Ted Orland had already been on board for about two years, working Monday through Friday. Ansel, not personally having any concept of “time off,” wanted to work seven days a week and hired me to work Friday through Monday.

In the darkroom next to Ansel’s 8×10 horizontal enlarger. The “burning” card I’m holding is a great example of Ansel’s sense of mirth! 1985

Ansel’s routine was to print in the morning during the regular week and do the selenium toning and washing in the afternoon after lunch. Being Ansel’s regular assistant, Ted would be in the darkroom for the morning sessions, and I would be called in to help with the toning and washing. In those days, “archival” print washers were anything but mainstream, and things were pretty basic in the Carmel darkroom. Prints 11×14 and smaller were washed in a big rotating “squirrel-cage” washer, and 16×20 and 20×24 prints were all washed by hand – moving batches of prints from one tray of clean water to another, dumping the first tray and filling it with clean water, moving the prints back to that tray and dumping the second tray, and so on, until maybe 10 or 12 exchanges had been made. Tedious and exhausting, but as it happens that process uses relatively little water and gets prints extremely clean.

After I had been on the job for several months, Ted left to carve out his own career, and I was then “first” (and actually only) assistant. I wasn’t married or busy with a lot of activities during the weekends and often popped by the house, helping out with this-or-that on a Saturday or Sunday, so my old position of Friday-to-Monday assistant was left vacant.

So now, the darkroom truly came to be my domain. What an experience!

Setting the Stage

Ansel’s darkroom was purely functional and consisted of nothing elaborate. In fact, nothing about Ansel was elaborate! He drove a Ford LTD which he bought used. His “sound system” consisted of an old mono amplifier, an old turntable and one speaker built into a wall. He rarely turned it on. Except for the Hasselblad, even his camera equipment was a mish-mash of rather tattered gear. One lens didn’t even have a brand name on it, but it sure was sharp!

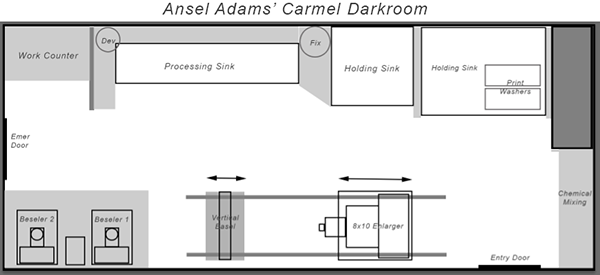

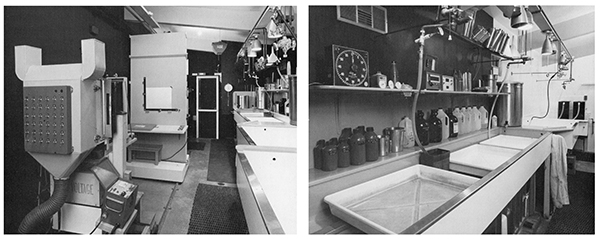

The darkroom itself was long and narrow, with three sinks taking up most of the length of one wall and enlargers along the other. One end of the darkroom, next to the pocket entrance door, was a chemical-mixing counter with various chemicals on shelves above, and drums of Hypo crystals below. At the opposite end of the darkroom there was a “panic door.” This was intended as an emergency exit in case of earthquake or other calamity. (Ansel’s nose was broken in an aftershock of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and he was somewhat fixated on that particular risk!)

The layout of the darkroom was principally engineered to accommodate the making of “mural” sized prints. His 8×10 enlarger was built by San Francisco’s Adolph Gasser out of an old 11×14 studio camera and set up to project its image horizontally. The machine ran on tracks on the floor and projected an image on an 8-foot tall vertical easel which also rolled on the same tracks. The lightsource consisted of a bank of 36 50-watt reflector bulbs, each on its own on-off switch. If Ansel wanted to give a general “dodge” to part of an image, he could turn off the lamp illuminating that region. The easel was faced on front and back with metal sheet, so paper could be attached firmly with magnets. A roll of mural paper could be inserted over a crossbar at the top of the easel and the paper pulled down like a window blind and held flat with magnets. On the opposite side of the easel and 8×10 enlarger was a counter which held two 4×5 Beseler MCRX enlargers. One of the Beselers had an innovative lightsource (Codelight) for printing on variable-contrast papers, and it could be turned towards the rolling easel and tipped up for horizontal projection in case he wanted to use it for big prints. The other Beseler had a condenser lightsource and was rarely used except for demonstration.

One staple of nearly every darkroom was absent in Ansel’s–an enlarging timer. There wasn’t one. Being a musician from his early teens, he was accustomed to counting beats, and had an electronic metronome set at 60 beats per minute. Every print he ever made in a darkroom of his own was made by simply counting seconds! This augmented his creative control immensely. Time was not something some gizmo measured and ruled, time was a deeply rooted internal feeling for Ansel. Twenty-two seconds felt like twenty-two seconds!

On the sink side, there was a long, fairly narrow sink for processing, with a ledge at the back for chemical containers and a wide ledge at the left and right for developer and fixer containers. On the left there was a 15-gallon stainless tank that held the Dektol stock solution, and on the right there was a 25-gallon tank that held the F-6 formula fixer we mixed from scratch. A shelf over the back of the sink held the metronome, various graduates and sundries. To the right of the processing sink was an approximately 3×3-foot print holding sink. To the right of that was another large sink, about 4×6-feet which held the squirrel-cage washer and maybe another rinse tray. If Ansel were making mural prints, the equipment could be removed from the sink and a wet 42×60-ish mural print could be laid flat.

In use, with the door closed on the long, narrow room, with white lights off, amber safelights on, water running, exhaust fans on and the rhythmic beep of the metronome, it had all the feeling of being in a fantasy submarine!