Where do you focus, and how does the aperture affect an image?

In a certain way, the opening question should be the other way around! There is a law of physics that governs the relationship between shutter speed and aperture (f-stop). Shutter speeds are pretty easy to understand: 1/60 second is one half as much time as 1/30. F-stops are a little different: f8 is one half the light of f5.6, which is half the light of f4! The point is, for any shutter speed/f-stop combo, one-half the exposure time with twice the light equals the same total amount of light given to the film – or pixels. 1/60 @ f4 = 1/30 @ f5.6 = 1/15 @ f 8.

There is always the inescapable relationship between exposure time and aperture. If you are photographing a sports event, you will likely go with a fast shutter speed and let the aperture fall as it will. This article will “focus” on aperture as primary.

F-stop #s versus depth-of field. A lens can only truly focus on ONE plane. With a perfect lens, that plane would be equally sharp at any aperture – but everything nearer or farther would rapidly become unsharp. Increasingly smaller apertures reduce this apparent unsharpness, increasing what is called depth-of-field. The smaller the aperture (f16 is smaller than f4), the greater the apparent sharpness.

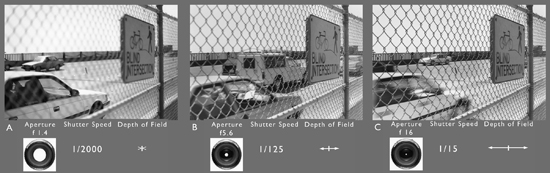

In the example above, figure A is focused approximately on the line of traffic in the foreground. The chain-link fence is way out of focus, as is the distant railing. The wide-open aperture (f 1.4) necessitated a very fast shutter speed resulting in the cars frozen in time. Figure B is with the lens stopped down 4 stops (f 5.6). The point of focus was not changed, but the fence is now a good deal sharper, as is the distant railing, but at the now much longer exposure time, the nearby car, while still sharp in focus, is blurred in time. Figure C is still focused in the same place but the lens is now stopped down 3 more stops to f 16. The fence now appears to be quite sharp as does the distant railing, but the car is now quite blurred at 1/15 second. (Note: it is a total coincidence that the images seem to show the same car!)

Most fixed-focal length lenses have an engraved scale allowing you to evaluate how much apparent sharpness (depth-of-field) you can get at various apertures. The example above shows a Hasselblad 80mm lens set at f 22. As the lens aperture is stopped-down, the depth of field increases in the proportion of 1/3 toward the lens from the plane of critical focus and 2/3 beyond the plane of focus. Figure A above shows the lens focused at about 3.3 feet, and at f 22 the depth of field runs from 3 feet away to 4 feet. Figure B shows what would happen if we did a landscape with the lens focused on infinity. The image would only be “sharp” from about 17 feet away to distant mountains. If we instead focused at 17 feet (this is called the “hyperfocal” distance) the image would now be sharp from about 9 feet to the mountains (Figure C).

There are two ways to plan how to make this work. One way is to choose your aperture first and see how much depth-of-field you get, and the other is to find out what aperture you need to work with and then see how much depth of field you need to work within. Let’s say your camera is on a tripod, and you want as much as possible near-and-far to be sharp. Take the Infinity mark on the lens and place it over the engraving for your smallest aperture. The lens is now focused automatically at the hyperfocal distance and you can read the depth of field on the focus scale of the lens. In this example (Figure C), f 22 gives you a pretty sharp image from about 9 feet to infinity. Lets say the camera is NOT on a tripod, and you can’t manage to stop down to f 22, but only to f 8. In this case, you would place the Infinity mark over the f 8 index. You would now see that the image would only be sharp from about 20 feet to infinity (see green arrows, figure C).

What if your lens doesn’t have markings? A lot of modern zoom lenses have distance scales, but no depth-of-field markings. If this is the case, you can find the hyperfocal distance by putting the nearest subject and distant subject marks on the lens an equal distance from the central focus mark. If your camera has a “depth of field preview” button, this can be a useful aid in seeing just how much is sharp – or not! But the actual depth of field for any given f-stop will just be a guess.

One bit of fun with f-stops: Selective Focus! Sometimes, you can make a stronger statement by limiting how much is in focus. Just leave the lens at its widest aperture. The figure on the left was done with a 200mm lens at f 4.5 focused exactly on the near marker, and the figure on the right was done at f 22 with the lens set at the hyperfocal distance.

One last thing I’d like to comment on in this writing: lens quality. Photo gear can be expensive, no doubt about it. Especially at an entry level, the prospect of getting an off-brand lens for a lot less than the brand that has your camera’s name on it can be awfully tempting. In these days of computer-aided engineering design a “Brand X” lens can be quite good – but there is an equally good chance that it will not measure up to the quality or durability of a top brand. One of the reasons being that the Brand X lens manufacturer can cut a lot of production cost by using much looser manufacturing tolerances than the top brands. The glass itself may well be of lesser quality. If you need to save dollars, look for quality used gear from a reputable source.

Hopefully, all of this will help you have a better understanding of the relationship between your vision, your lens, and your results!

Nick